- Home

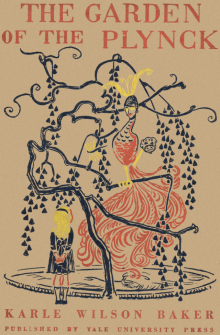

- Karle Wilson Baker

The Garden of the Plynck Page 4

The Garden of the Plynck Read online

Page 4

Sara was determined, when she shut the ivory doors behind her the nextmorning, to do two things, no matter what happened; first, she wouldput her dimples in the dimple-holder immediately; and, second, shewould go right on to find Pirlaps, and not be beguiled into lingeringaround the pool by the fascinating talk of the Plynck and her Echo.For, ever since she left him, she had been thinking of the offerPirlaps had made to take her to see his relations; and she had beengrowing more and more curious and interested.

And this time she did remember her dimples; she saw them sparkling onthe whipped cream cushion, all safe and contented, before she so muchas lifted her eyes from the blue plush grass. But alas, for herresolution not to loiter! For although, on the other days, there hadbeen such a variegated murmur of delighted sound--the Echo of thePlynck in the pool, and the lovely crackling of breaking rules, andthe deep-blue singing of the Zizzes' wings, and the melodious snoringof the Snoodle (like that of a tuning-fork when it sleeps on its side)--yet everything had been as still and motionless to the eye as anApril daydream. But this morning it was the other way around. Not asound was to be heard; but what a scene! You see, for the first time,the Snoodle was awake, frisking soundlessly around the fountain; andthe Plynck--the Plynck was flying!

Now, it is true that a Plynck at rest is a beautiful sight; but it isnothing to the charm and wonder of a Plynck in motion. (The same, aswe shall see in a moment, is true in a lesser degree of a Snoodle.)Its long, rosy plumes, like those of an ostrich, only four times aslong, went waving through the air with an indescribably dreamy grace;and now Sara could actually see the perfume, which before she had onlysmelled. It rained down through the air, as the Plynck circled slowlyround and round the fountain, and looked rather like a sort of goldenspice. And as Sara stood watching, spellbound and sniffing, she knewshe had been mistaken in thinking that, there was no sound at all.There was just one: a little soft, straining sound the Plynck'scerulean Echo made as it circled round and round in the pool and triedto keep up with the Plynck. Her motions would have been exactly aslovely as those of the Plynck, if they had not been just a triflelabored, owing to the difficulty of flying under water; and herbreathing was distinctly perceptible. Sara could hear it, too; and itsounded like the ghost of a dead breeze in a pine-top.

As soon as Sara could take her ravished eyes from the sight, shelooked down to see what was nuzzling about her shoe-buttons; and, justas she had suspected, it was the Snoodle, frisking and tumbling androlling about her feet to make her notice him. And, indeed, when hewas awake, the Snoodle was irresistible. Not that he looked likeanything Sara had ever seen before. He might, perhaps, have lookedlike a dog, except that he was so very long--his length, indeed, gavehim a haunting resemblance to a freshly cooked piece of macaroni.(Sara was later to find out the reason for this; but at the moment shewas puzzled, just as you are when you meet a stranger who looks likesomebody else, and you can't remember who else it is.) And his head,which was not very clearly defined, was finished off with a neatlittle cap that looked like a snail-shell, and seemed to be fastenedto him. His eyes, which stuck out several inches in front of his faceon long prongs, were delightfully mischievous and confiding; and hewas covered with the most beautiful snow-white, curly hair. But he hadone drawback; and Sara discovered that when she started to pick himup. It was a sort of little window in the exact middle of his back,with an ising-glass cover, like the slide-cover of some boxes. Theminute you touched him, this little slide drew back, and from withinthere escaped an odor of castor oil. It, too, was distinctlyperceptible; Sara could even smell it. As soon as she did so, sheherself drew back, and contented herself with looking admiringly at theconfiding, playful little Snoodle.

As she stood watching his pretty antics she became aware that theSnimmy's wife had stopped her work and was watching them with a grimsmile. Sara saw that she had just unscrewed the knob of the prose-bush,and was still holding the doorknob and the corkscrew in her hand. Asfar as Sara could tell, the doorknob seemed as neatly hemmed as ever;so, overcome by curiosity, she asked the Snimmy's wife what she wasgoing to do with it.

"This is the day to unhem it," she answered rather glumly. "I unhem itevery Pinkday, and hem it every Lilyday. I used to hem it only oncet amonth, but Avrillia said that wasn't civilized, and whatever she says,goes. At least," she added, glancing up at the Plynck, who was stillcircling beautifully around the fountain, "she thinks so. And as longas I live neighbor to her it's sort-of up to me to respect herstandards."

Avrillia! Ah, now Sara remembered! She had meant to go straight tofind Pirlaps and Avrillia! She glanced around to see if she could findthe curly little path; but she could not really start until she hadasked a few questions about the darling little Snoodle.

"Is--isn't he lovely?" she began, aware of a vague necessity ofpleasing the wife of the Snimmy, if one wanted to find out anything.However, she was quite honest; she really did think the Snoodle waslovely--except for his drawback.

"You think so?" answered the Snimmy's wife, trying hard not to showhow foolishly pleased she really was. "He's the only child we have."

If Sara had thought a minute, she would not have asked the nextquestion--certainly not of so formidable a person as the Snimmy'swife. But she didn't think. She just asked, eagerly,

"Is he a--a sort of--dog?"

"A sort of _dog_?" echoed the Snimmy's wife, in the most outrageditalics.

"A--kind of--puppy?"

"A kind of--PUPPY?" said the Snimmy's wife, in perfectly witheringsmall capitals. Then she said, in the loftiest large capitals Sara hadever seen,

"HIS MOTHER WAS A SNAIL--SHE HELD THE WORLD'S RECORD FOR SLOWNESS. ANDHIS FATHER WAS A PEDIGREED NOODLE."

Sara looked at him in awe; now she understood the cap, and the prongs,and the extreme length. But, in spite of the Snimmy's wife's indignantmood, she had to ask one more question.

"But you said he was your child," was the way she put it.

"I didn't," retorted the Snimmy's wife, with undisguised contempt. "Isaid he was the only child we have. We have him, haven't we?" And withthat she sat down with her back to Sara on her own toadstool, andcurled her long white tail around the base with quite unnecessarytightness. Her nose was not quite so debilitating as the Snimmy's;still, it nearly stuck into the doorknob as she hemmed.

Sara saw there was nothing further to be got out of her, and she didnot wish to pick up the Snoodle on account of his drawback; so shedecided to go on to Avrillia's without further delay, and began tolook around her again for the little curly path. It was pink, thistime, instead of curly, but that made it all the more attractive; soshe struck into it at once, and went skipping happily toward the archin the hawthorn hedge. Just before she reached it she heard Avrillia'sthermometer go off, so she knew that she was on the right path.

The minute she got through the hedge she saw Avrillia, and, oh,loveliest of wonders! What were those? Flying around her hair,clinging to her silken skirts, dancing among the shell-flowers,swarming over the balcony, playing a dainty game up and down themarble stairs--oh, it was the children! The children were at home!

And when Avrillia saw Sara she came toward her with the loveliest lookof welcome, the children hanging all around her like rose-garlands.And if Sara had loved Avrillia the day before, she could simply findno words now to express her adoration. For Avrillia knelt down amongthe shell-flowers, and held out her arms (which were like the necks ofswans) to Sara; and she really seemed to see her this time. And whenshe smiled at her, her eyes were hardly at all wild, but quite playfuland gentle; and so sweet that Sara, for a moment, had a dizzyconviction that if she were a Zizz she would fly right into them.(Though, of course, the Zizzes' tails were bitter.) Besides, Avrilliaheld her at that minute tight to her breast, which was as soft as herown perfect, contrary mother's, and had, besides a most entrancing,faint perfume of isthagaria.

When she had finished hugging Sara, she held her off at arms' length,and said to her, smiling, in that lovely voice,

"Well, Sara, you

see the children are here. Aren't they nice?"

And once more Sara could find no words to express their niceness. Andshe could no more have described them to you than if they had been somany endearing young charms. But one of the queerest, prettiest thingsshe was sure about: their faces were all dimples! Moreover, they weremuch more becoming to them than ordinary features would have been.

"How old are they?" asked Sara, in the most delighted bewilderment.The friendly little things fluttered and chattered and chirrupedaround her in the most distracting way, brushing her face with theirwings in their eagerness to get acquainted, and even getting theirsilver sandals tangled in her hair.

"Well," said Avrillia with great exactitude--Sara had alreadydiscovered that Avrillia had a weakness for being consideredpractical--"fourteen of them are six and three of them are two andthirty are seven and ten are nine, and five are six months."

"My!" said Sara, in doubt and wonder. And right there she had asuspicion that that was one reason she had loved Avrillia from thefirst: she couldn't do arithmetic! To be sure, Sara herself couldn'tadd all that mixture in her head--at least not with all those lovelychildren about--but it sounded like a great deal more than seventy;and there certainly looked to be a million. So, as she stood and gazed,she said, more in wonder than with any idea of correcting Avrillia,"And you said there were just seventy?"

For a moment Avrillia's eyes again grew distraught and doubtful, andshe answered, uncertainly, "I think there are just seventy." Then shecalled to Pirlaps, who was sitting on his step in the light of aglorious flame-colored fog-bush, hard at work, "Pirlaps, have we hadany children since Sara was here yesterday?"

"Not one," said Pirlaps, smiling at her with a look of pleasantamusement. "Don't you remember that you dropped poems over the Vergeall day?"

"I thought so," said Avrillia, with relief, "but Sara seemed to thinkthere were more than seventy." Then her eyes fell upon the trousers ofPirlaps, who had risen and was coming toward them now, with Yassuhrolling along behind with the step.

"O Pirlaps," said Avrillia, her sweet voice full of reproach, "youhaven't changed your trousers! That's just the way things go," sheadded, beginning to look wild and worried and distraught, "when thechildren are here! I can't keep up with everything! And thethermometer went off fifteen minutes ago! I heard it, but I was busywith the children. And your shaving-water will be perfectly cold!" Shegrew more and more agitated.

"Never mind, Avrillia," said Pirlaps, soothingly, and Sara noticedthat his pleasant, cheerful ways always had a wonderfully calmingeffect upon Avrillia. "I'm going right in now to change; and then Ihave a plan that will straighten things out and please everybody."

"What is it?" asked Avrillia, looking more hopeful.

"It's too soon to tell yet," said Pirlaps, with a delightfully wiseair, and he went on up the steps, with Yassuh tumbling after him,leaving them all feeling very much relieved.

Avrillia, making a brave effort to recover her composure, beganplaying with the children again, and they were having almost asdelightful a time as if nothing distressing had occurred, when Pirlapsreappeared, all fresh-shaven and immaculate.

"Put the step out in the sun where it will keep soft, Yassuh," hesaid. "I shan't need it this afternoon."

They all stopped playing and looked at him in wonder.

"I'm going to take Sara to see my relations, as I promised her I would,"he explained, taking Sara kindly by the hand.

"Oh, that's lovely," said Avrillia, looking at Pirlaps gratefully outof her speaking eyes. "There's nobody like you, Pirlaps."

Pirlaps looked wonderfully pleased with himself; and, since there wasnot a bit of chocolate on his trousers, he looked unusually spruce andhandsome, too. Sara skipped along beside him delightedly; only,sometimes when she looked back, she wished she could stay withAvrillia while she was in such a lovely mood, and all thoseinteresting children. Still, Sara's dear, self-willed mother hadtaught her to be a considerate little girl, and she reflected that shereally ought not to bother Avrillia with another child, when shealready had seventy to look after. The thoughts of Pirlaps also seemedto be running in the same channel (indeed, Sara could catch glimpsesof them, trickling along under that thin, funny cap he always wore),and he presently said,

"It's too bad to bring you away when the children are at home, Sara,but you know they are a great deal of care to Avrillia, and whenthey're at home I try to do everything I can to relieve her. Now, yousee, she won't have to bother about my trousers for the wholeafternoon."

"But how can you get along without your step?" asked Sara. She knewthis was a personal question, but she felt, somehow, that Pirlapswould not think her impolite.

He looked down at her and smiled, just as her own father did when sheasked questions which showed her youth and inexperience.

"I'm not a step-man, Sara," he said, his eyes twinkling with amusementat her lack of information, "only a step-husband. When I'm away fromAvrillia I don't need the step."

All this time they had been walking along hand in hand. Sara noticedthat they had left the Verge behind, and were following a verypleasant sort of ridge, from which they could see down into a sort ofhollow for smiles and smiles, and, beyond the hollow, the buff-coloredhills and mountains that formed the walls of the amphitheatre. Therewere not so many Gugollaph-trees as there were in the Garden and alongthe road to the Dimplesmithy, owing to the different topography of thecountry; instead, there were a good many poker-bushes.

"My relations live in a colony," said Pirlaps. "There used to benearly seven hundred of them; but now there are only eight hundred andthree."

And just at that moment they came in sight of the colony. It consistedin a large number of odd, attractive-looking little houses groupedaround an open space covered with pleasant red grass, which Pirlapstold her was an uncommon. In the middle of the uncommon was a sort ofplatform, and upon the platform there was something which Sara, atfirst glance, took to be an enormous statue. But even at that distanceshe could see it move; so she hastened to ask Pirlaps what it was.

"Why, that's my Great-Great-Great-Great-Grandfather," said Pirlaps,with a good deal of pride. "He occupies the Post of Honor in thecolony, you know, because he's the oldest and the largest. He's reallygreat, and quite pleasant; you'll enjoy meeting him."

By this time they were going down a little shady road that ledstraight to the uncommon. Sara was so struck by the large number ofcurious and interesting people she saw on all sides, going quietlyabout their regular occupations, that she could hardly look where shewas going. But Pirlaps led her right to the foot of the post, and thefirst thing she knew he was introducing her. "This is Sara,Great-Great-Great-Great," he was saying; and Sara looked up and saw,sitting in a sort of easy chair on top of the post, the very largestperson she had ever seen. In size he was a veritable giant, or even anogre; but anybody could see that in disposition he was as far aspossible from being either. Indeed, his disposition was evidently verylike that of her own grandfather (who wasn't great at all, at leastnot in comparison with this one), even to the bag of marshmallows inhis pocket. Sara could see it sticking out--but such enormousmarshmallows! Why, each one was larger than the biggest, fattestsofa-pillow Sara had ever seen. And, of course, beside themarshmallows, the Great-Great-Great-Great had beautiful white hair,and twinkling eyes, and all the usual equipment of a grandfather.

"Why, good afternoon, Pirlaps," said the Great-Great-Great-Great, in alittle high, cracked voice that seemed very odd. ("As they get greater,their voices get smaller," explained Pirlaps, who had noticed thatSara jumped when the old gentleman spoke.) "Would you like amarshmallow?" he continued, tossing one down to her; and Sara sawthat it would have tipped her over, as Jimmie's missiles sometimes didwhen they had a pillow-fight, if Pirlaps had not caught it. While shewas wondering what would be the polite way to eat so huge amarshmallow, she saw the other Grandfathers coming toward her. Sheknew them because there were four of them, marching in single file,with their hands on each other's shoulders.

The Great-Great-Great, whowas next in size to the one on the Post of Honor, was leading, andthey were arranged in order down to the plain Grandfather, who was notmuch above the usual height.

At the same moment she saw the Grandmothers coming from theopposite direction, in the same manner. Only, the mate to theGreat-Great-Great-Great was leading, and they were coming straighttoward the vacant Post. Sara watched them with extreme interest. They,too, were of quite the usual grandmotherly pattern, but were equallyvariable and extraordinary in size. When they reached the Post theymade a sort of living stepladder, like the acrobats in the circus; thatis, the plain Grandmother stooped over, like a boy playing leapfrog,and the Great mounted on her back; then the Great-Great mounted on herback, and so on, until finally the Great-Great-Great-Great got upon thevery top and so stepped upon the Post. She took her seat in anarm-chair like the one on the other Post, and Sara noticed that herkerchief was exactly the size of one of Mother's hemstitched sheets.She was indeed a handsome, venerable and distinguished-looking oldlady, if you stood far enough away to see her all at once.

"Well, Sara, should you like to see the cousins?" asked Pirlaps, whenthis interesting manoeuvre had been completed and the otherGrandmothers began to disperse. "We'll be just about in time for thedrill."

"Yes, indeed," cried Sara, who was very fond of watching drills. SoPirlaps led her to a level place which he told her was the cousins'drill-ground. It was hard and smooth, and marked off with lines like atennis-court, only much more intricately. And there were numbers ofcousins standing about, each one looking very erect and alert, withhis hand on the back of a chair. Just as Sara came up, the captain ofthe cousins stepped out in front and called, "Attention!"

The cousins looked so attentive it was almost painful.

Then he called out, "First Cousin once removed!" and the First Cousinmarched out very stiffly and set his chair down accurately on thefirst mark, after which he sat down in it with military precision.Then the captain called, "Second Cousin once removed!" and the SecondCousin marched out and sat down in the right place quite asimpressively.

Well, you can imagine how it went on, as far as Tenth Cousin eighthremoved; and after they had gone through it straight the captain beganskipping them around. It was very lively and exciting; but whenPirlaps heard Sara give a little sigh, and asked her, with a twinkle,how she liked it, she was obliged to answer, "I like it, but--it makesmy head turn around. It's so much like arithmetic."

"That's what Avrillia says," answered Pirlaps, smiling. "Well, let'swalk around a bit. And then I'll show you the Strained Relations."

Sara thought that sounded very interesting; and, besides, she was gladto walk after standing still so long. So they strolled about, enjoyingthe pleasant afternoon, and the oddity of the people and their ways.There were any number of step-relatives, mothers, fathers, brothersand sisters, sitting around on their various steps, or carrying themjauntily under their arms. She noticed that none of them had a servantto carry them, however, from which she concluded that they were not sowell-to-do as Pirlaps. But then, none of the steps were of chocolate.They were of various materials, however, even yellow.

Once, in crossing the uncommon, they met one of Pirlaps' half-sisters.She was divided lengthwise, and so had only a profile; but, as herprofile was very pretty, the effect was not at all unpleasant. Whilethey were talking to her, one of his half-brothers came up, but he wasdivided crosswise, and so had no back. However, from the front, ofcourse, you hardly noticed it.

"Well," said Pirlaps, at last, glancing at the small clinicalthermometer he carried, "we'll just have time to take a look at theStrained Relations, and then I must get back and help Avrillia vanishthe children."

He led Sara to a distant corner of the uncommon that was fenced offfrom the rest by a high wire netting. It looked rather like the highnets about a tennis-court, except that it was made of silver wire,with a mesh as fine as a milk-strainer. Inside the wire, in a sort oflittle private park, she could see a number of very haughty-lookingpersons moving about.

"Don't speak to them," said Pirlaps, as they drew near. "They'reentirely too snobbish to be spoken to."

Sara approached in awe, and they stood gazing at the pale,supercilious-looking creatures, who returned their gaze throughmonocles, lorgnettes, and other contemptuous media.

"You see," explained Pirlaps, "nobody speaks to them. Every time theygo in or out, they pass through the strainer, and that strains out allof their red corpuscles and leaves only the blue. That's why they areso superior and exclusive. Of course, too, it makes them very thin,and gives them that sheer, transparent look." And, indeed, Saranoticed that she could see quite through one of the thinnest ones, whowore a very high-necked dress buttoned in the back.

Pirlaps was now growing anxious to be at home, so after saying good-byto the important personages on the Posts of Honor, they started back.

As they drew near, they saw Avrillia in the rose-garden near thebalcony, looking very lovely as she moved among the flowers.

"Ah," said Pirlaps, "she's already vanished them. She's gatheringrose-leaves for tomorrow's poems."

As he spoke, Avrillia, looking up, waved a blue rose to them, anddisappeared within the house. In a moment she reappeared, wearing thesweetest smile Sara had ever seen.

Pirlaps looked greatly pleased and touched. And no wonder; forAvrillia was coming out to meet him, bringing him his step with herown hands.

The Garden of the Plynck

The Garden of the Plynck